Sylvia Plath's wall, desk, and pocket diary/calendars offer the researcher a wealth of biographical and bibliographical information about her life, work, and times.

During her first year at Smith College, if Plath kept a calendar for her first semester its whereabouts is unknown. But the Lilly Library holds a wall calendar for 1951 which features crucial information about Plath's assignments, social life, and so much more. The calendar for 1952 is a desk calendar; as is the incomplete one for 1953 (due to her suicide attempt and recovery, entries slow down and cease by 24 August). The 1953 calendar features images of Germany and had has days, months, and other information all in the German language. If she kept a calendar for the spring term of 1954 its location is unknown.

|

| 1954-1955 Calendar |

From the summer of 1954 when she was at Harvard Summer School until the Spring of 1957 when she completed her degree at the University of Cambridge, Plath fairly regularly kept a log of her actions in the form of pocket/purse diaries. There were periods where she also maintained desk calendar and sometimes had two going simultaneously. On her long breaks when at Newnham, her desk calendar remained in Whitstead, virtually silent and unaware of what was going on in her life. However, the smaller format pocket calendar, which she kept in her purse, fairly bursts with all the life she was living.

|

| Summer-Fall 1955 Calendar |

|

| 1956-1967 Calendar |

The 1956-1957 calendar was used consistently at the start of her second year as a Fulbright until she moved from Whitstead to 55 Eltisley Avenue, at which point the usage seems to dry up. It has always left me stumped that suddenly in spite of their purpose of helping Plath to recall her activities day by day, they undoubtedly offered assistance in ordering her life.

From 1957 to 1962, there are no known calendars. In 1962, Plath kept a Letts Royal Office Tablet Diary which is held by Smith College. Which is peculiar considering that one would have been vital to have during her teaching year at Smith College from September 1957 to May 1958. Also, during the Boston year, September 1958 to June 1959, as well as the cross country tour and Yaddo leading up to their December 1959 departure for England, a calendar will have been crucial to both Plath's and Hughes' lives.

These absences notwithstanding, there is evidence, actually, to their one-time existence. Where? In her journals. In 2021, I read the journals in full for the first time in many years. Previously dipping in and out or looking for something specific, I felt it was overdue to read it cover-to-cover.I was intrigued by Plath's own references to the journal as an object itself, but I noted a few instances where she refers to exterior documents she kept, such as these missing calendars. Some are explicit and some are rather vague, such as the first instance from 9 February 1958 in Northampton: "Now for a picture, enough of this blithering about calendar engagements" (327). This could be theoretical calendar engagements, those of the responsibilities she faced as an educator of first year students taking an English course.

However, a few pages later on 18 February, Plath writes "The church bells have begun and done their noon hour chiming and I, back from the clear sheer blue air, unaccountably exhilarated, poise on the brink of grim work, leafing through my calendar, counting 4 weeks to spring vacation, seven & a half weeks until my books begin" (332). There it is: a reference to a physical calendar. Was it a pocket calendar, a desk calendar, something officially issued by Smith, perhaps? In March she reiterates her impatience for Spring Break, "I count & recount calendar weeks as if an idiot telling beads toward the second coming" (348). And then shortly there after on 29 March 1958, "Looked through & through my calendar: eight weeks: seven actual teaching weeks" (358) and again on 6 April, " I count my calendar" (363).

Tantalizingly, her journal entry for 13 May 1958 reads, "This week on my calendar looms full and scrawled with meeting, dinners, classes, and the deluge of my last and long papers to come and engulf the weekend - then next week - two days & my classes done with, only James to fill up on and then Arvin's last exams" (382). Very much suggestive of a physical, inked up document. This is all for 1957-1958.

It is back to the theoretical a year and eighteen days later on 31 May 1959 in Boston: "A heavenly, clear, cool Sunday, a clean calendar for the week ahead, and a magnificent sense of space, creative power and virtue" (486). Although this calendar reference seems to refer to something real, there is nothing tangible with which we can work. Or, is there?

Held by Smith College is a document that suggests that there was in fact a physical object, an actual calendar used by Plath in 1959. On the back of a page ripped from a calendar are some financial calculations for Plath's and Hughes' Boston 5¢ Savings Bank account. The notes date from 1960 to 1961. This bank account was used for earnings from creative writings, so there are notations in there for Ted Hughes' "Hawk Roosting" in the Spring 1960 issue of Partisan Review, payments for works which appeared in that time frame from The Nation, Atlantic Monthly, Texas Quarterly, Partisan Review, Mademoiselle, Harper's, and The New Yorker. There are also some calculations for their Newton-Wellesley bank account.

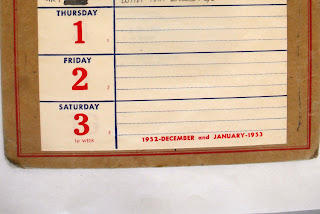

But that is the verso. Well, now we get finally to the heart of the matter. On the recto of this page torn from a desk calendar are blank dates for 23 to 26 December. A Wednesday to a Saturday. The bottom, lower half of the page.

|

| Courtesy of Smith College Special Collections |

Christmas was a Friday and as you can see, above, the date is circled in Plath's distinctive black pen. The dates themselves are blank, void of entries. Given that Plath was in-between residences--situated physically at the Beacon in Heptonstall--at the time this is not surprising for the calendar to be blank. For what it is worth, this is the same style desk calendar that Plath used for 1952.

In the 1950s, Christmas was on a Friday in 1953 and 1959. We know Plath kept German calendar for 1953; and, at the time she was in McLean, anyway. So for my druthers this calendar clearly dates to 1959, especially considering that the financials on the verso relate to 1960 and 1961.

But where is the rest of the calendar?

If you benefited from this post or any content on the Sylvia Plath Info Blog, my website for Sylvia Plath (A celebration, this is), and @sylviaplathinfo on Twitter, then please consider sending me a tip via PayPal. Thank you for at least considering! All funds will be put towards my Sylvia Plath research.