On 5 July 1943, Sylvia Plath wrote to her mother from Camp Weetamoe in New Hampshire that she consumed "5 Tollhouse cookies" (Letters Vol I, 10). From Smith College seven years later, Plath casually mentioned that if her mother wanted to send her something that "Toll house cookies will be most welcome. I’m too hungry to share many, so will eat them with my before-bed glass of milk" (202). By summer 1951 when she was living with the Mayo family in their Swampscott house, Plath was making them herself (350). Her love of Toll House cookies is rather legendary. (What Plath called Toll House cookies are, largely, to us, the simple chocolate chip cookie). There are about sixteen references to these cookies between the two volumes of letters and just one in her journals.

Of course, I was inspired to try to recreate the photo of Plath with cookies. Sadly, I did not have a red bandana.

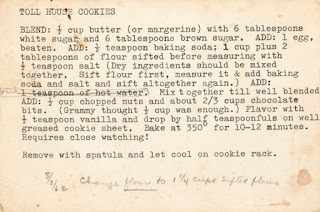

When the batch of Plath's recipes cards (and rolling pin) hit the auction house last summer (Lot 45), many were excited about the Tomato Soup Cake recipe. Being a lover a chocolate myself, I wanted to see the Toll House Cookie recipe and to try it, too. Below are the steps to take, slightly modified (not exactly transcribed), from Plath's recipe card.

Blend: 1/2 cup butter (or margarine) with 6 tablespoons of white sugar and 6 tablespoons of brown sugar.

Add: 1 egg, beaten.

Add: 1/2 teaspoon of baking soda, 1 cup plus 2 tablespoons of flour sifted before measuring with 1/2 teaspoon of salt

Dry ingredients should be mixed together.

Sift flour first, measure it, and add baking soda and salt and sift altogether again.

Add: 1 teaspoon of hot water.

Mix together until well blended.

Add: 1/2 cup chopped nuts and about 2/3 cup of chocolate chips. (Please note: "Grammy" Schober though 1/2 cup was enough. Not that anyone asked, but I could not disagree more strongly with "Grammy")

Add: 1/2 teaspoon of vanilla

Portion out onto a greased or papered cookie sheet 1/2 teaspoonfuls of the dough

Bake at 350 for 10-12 minutes. "Requires close watching!"

Because she could not help herself, Aurelia Schober Plath, in the midst of her daughter's marriage crumbling, of course, made two amendments to the recipe card which she (arrogantly?) dated 2 August 1962. One was to "omit" the step about adding a teaspoon of hot water. And the other was to "change flour to 1 1/4 cups sifted flour".

An early recipe from 1939 was printed in the below Lincoln, Nebraska, newspaper.

The recipe appears to be halved compared to some current recipes at which I looked (this, for example).

Plath herself was photographed circa 19-23 June 1955 holding three Toll House cookies when she was at the beach at Ipswich, Massachusetts, too!

The other day, my wife and I made Plath's recipe for Toll House cookies and the result was wonderful.

We have also made Plath's heavenly sponge cake twice and both times were a righteous success.

All links accessed 12 and 18 June 2022.

If you benefited from this post or any content on the Sylvia Plath Info Blog, my website for Sylvia Plath (A celebration, this is), and @sylviaplathinfo on Twitter, then please consider sending me a tip via PayPal. Thank you for at least considering!